Germans aren’t known for their love of small talk. If you ask a stranger «Wie geht’s?» («How are you?»), don’t be surprised if you’re met with a puzzled or suspicious look. Some might even take the question at face value and respond with a detailed account of their current mood, complete with a rundown of their life’s latest triumphs and tribulations. This level of candor can feel overwhelming, especially if you were just expecting a polite «Gut, danke!» («Fine, thanks!»).

Germans are known for their directness, which can sometimes come across as brusque. But it’s not rudeness—it’s just their way of communicating. They value honesty and clarity, and they say what they mean without sugarcoating it. Tactfulness can sometimes be seen as vague or even insincere, so don’t be surprised if they skip the pleasantries and get straight to the point.

If this description sounds a bit intimidating, brace yourself for Berliners. The manners of the Berliners are a fundamental challenge for decent people. The locals are considered to be rather grumpy, to say the least. They like to curse, swear, and grumble. Berliners are known for their «Berliner Schnauze»—literally «Berlin snout,» better translated as impudenc

«One doesn’t get very far with politeness in Berlin,» Goethe once snorted, «because such an audacious race of men lives there that one has to have a sharp tongue to keep oneself afloat.» He summed up Berlin in a single word: «crude.» As the saying goes, «They don’t mince their words.»

In Berlin, words like «please,» «thank you,» and «sorry» are used sparingly. The limits of friendliness are narrow, and apologies are rare. If someone bumps into you on the street or in a crowded subway, don’t expect an apology. Instead, you might hear something like: «Hey, don’t you have eyes in your head? Watch where you’re goin!» Even if the fault is clearly theirs, Berliners are more likely to snap than to apologize. And if a Berliner does apologize, he usually doesn’t mean it.

The psychology behind the concept of an apology is completely lost on them. You can tell when they stare at you in astonishment when you apologize to them, even for the smallest thing. You will almost never get a positive response, such as «It’s OK» or «No problem.» Rather, they are then more likely to think that you have caused them great inconvenience and start complaining about it.

Ask someone for a direction, and you’ll get a stroppy answer: «Am I Google or sumfin’?» Or «Don’t have a map on you, eh?» Ask three different people, and you will get three different answers. At least one of them is deliberately sending you in the wrong direction. You would think that where there are so many people in such a small space, there would be more consideration for others. In cultured places, people understand how much gentleness makes everything easier. Not in Berlin.

Any guide will tell you that the Berliner Schnauze is a mixture of coarseness and warmth. You have to learn how to take it, they like to say in defense of that rude behavior and short-tempered cheekiness. Berliners are «quaint» and «authentic,» very special people with strong personalities. You just have to get to know them, and they will reveal an extremely funny and companionable nature. They have a good and honest heart. Hard on the outside, soft on the inside, and so on.

The dialect was somehow totally cool, and you would like to be able to talk like that. The e-learning platform Babbel kindly calls Berliner Schnauze «the cult language of the capital» and even offers tips for those who want to learn how to speak like a Berliner. Who wouldn’t want to talk like someone whose ancestors just made it out of the swamp?

If there’s one thing Berliners are not, it’s being authentic. These perverters of language are just assholes. Vulgar, unreflective and vile. Dull, empty shells filled with frustration, aggression, and resentment. Ruthless, abrasive, and opinionated. Shamelessness, tactlessness, and sheer stupidity are their authenticity.

Every half-wit thinks he is unique. They think they are the best at everything. The one thing they all have in common is that they annoy each other. Young people annoy old people, bourgeois people annoy punks, artists annoy proles, and the other way around. Everyone gets on each other’s nerves. They even find kids to be a pain.

Sure, they’ll all tell you it’s great to live here, yo. Especially those who have only been here for three days. The Urberliners (that is, born-and-bred) know better. They are so jaded that they no longer expect anything from life. «So what?» is their favorite response to everything from «The neighbor just died!» to «You’re fired!» Even if the Russians stormed into their bedroom and told them the world was going to end in ten seconds, they’d be blah.

They know they’re jaded, but they don’t bother to reflect on it or come up with a solution. Because, duh! So what? They are fed up with the human scum they see in the mirror, and the only enthusiasm they have left is to do as much damage as possible to the rest of the world. Their snotty babble is nothing more than an attempt to inflict their own inferiority on as many people as possible.

Unfriendliness and poor service also prevail in Berlin’s pubs and restaurants. Even in the best restaurants, guests are poorly served, downright bullied. The waitresses only work there anyway because they’re shagging the boss. Smiling costs extra—it only gives your face a sore. All the energy goes into the food—you’ll get an astonishingly uniform mush. Snotty waiters and waitresses make sure of that.

The latte is served by grumpy but probably good-looking baristas. They only communicate with grunts and push your coffee across the counter with grumpy faces after making you wait forever. The foam of the latte looks like bathwater two hours later. No amount of charm will stop them from blaming you for making them do this demeaning job that they are far too great for.

Insult humor is a local pastime. They call it «frech wie Rotz»—«cheeky as snot.» If there’s one thing Berliners can’t do without, it’s this. The further down the ladder he is, the harder he has to kick. Germans have no sense of humor, and the world knows it. The Berlin «sense of humor» is the worst. They love to explain the world to you. Many find it funny to make jokes about marginalized groups. Life is one big joke. And not a very good one.

It’s actually just an asshole comedy. Berlin humor has destroyed countless lives and brutally trampled on freedom and human dignity. «IT’S JUST A JOKE!» The bus driver who waits in the rain until you reach the bus stop, then slams the doors in your face and drives off. That’s a good one. Everyone laughs. Drum roll. Curtains.

Anyone who has lived here can tell such stories about this supposedly laid-back city. There’s even a group on Facebook where expats share their experiences with particularly blatant examples of rudeness in parks, stores, offices and train stations. These are not just anecdotes: In a Time Out Index survey, Berlin was named the rudest city in the world. Other cities would be embarrassed, but Berliners don’t have much else to be proud of.

We can only speculate as to why Berliners have such difficulty with humor. Perhaps it is because it was from Berlin that all people with a sense of humor were imprisoned in camps and then systematically murdered. Or perhaps humor requires a certain minimum number of hours of sunshine because existence determines consciousness. Winters are cold, dark and even colder, and the darkness is very long—sometimes the sun doesn’t shine for months. People can become very troublesome and even hostile, depressed, or crazy at this time of year. Some people can’t get to sleep, some can’t get up. Yesterday 12°, and today 30°—that’s normal here in the summer. Avoid Berlin in winter and in summer—it really sucks.

Lifestyle guides say you have a choice, and you can choose to be positive. What if you choose to be in a bad mood? Life has no happy ending. All their jokes at the expense of others reveal a lot about themselves. Berliners think they are entitled to a medal for their presence on this planet, but no one comes to hang it around their necks. They think they are in the right, but no one, damn it, notices their brilliance. All the cursing and blathering reveal a glaring lack of sophistication. Berlin was and is a dead and alive hole. Populated by people from the provinces who secretly long to return to Shittanburg.

The true meaning of the term «Berliner Schnauze» becomes clear after a few weeks on the Spree. The metaphor of the «school of life» takes on a new meaning. It really is not for the faint-hearted. If you’re insulted by a Berliner and keep quiet, you’ve lost. The Berliner expects you to shout back. In Berlin, it’s okay to behave like a sociopath. If you are not rude, but rather subtle and sensitive, you will go down easily. If you like bad manners, you’ll love Berlin. Nowhere else can you find such cynical, vile, hostile misanthropes. Always sad, rude, and aggressive.

Kind and positive people irritate the hell out of them. It bothers them to see people who have their lives figured out and feel good about themselves. Because they themselves just don’t get how these people do it. Because Berliners secretly hate themselves, but they don’t say so. They lie to themselves. They are mean and soulless, and you can feel it in the air. If you have no respect for yourself, you have no respect for others.

Only when they can be mean to others do they feel anything at all. It makes them feel comfortable and happy. They have a masochistic streak, and all their bitching is really just a begging for humiliation. Every kind-hearted and gentle person should stay away from these hateful people and this ugly shithole. Berlin means tristesse, incivility, and hostility.

Don’t expect anything from Berliners. They are mostly just hypocrites and posers. They talk a lot and promise the moon. But when it comes to the crunch, they’re gone faster than you can blink. In the world of these losers and boozers, it’s all about them. Those who look for friends at parties, bars and clubs will get what they deserve. You won’t meet a partner, a soul mate, real friends or even people who won’t screw you over at every opportunity. No one is interested in you. Who would want to really get to know people who only live in a city because it’s a great place to get wasted and live a slacker life of sex, drugs, and parties?

You won’t have any fun, despite all the drugs you’ll be offered. On a cold winter morning, you will end up as a bloated mess on the sidewalk, foaming at the mouth, best ignored, but most likely pissed on by a dog and then by its owner. And he’s probably not even drunk. The full Berlin experience.

The Berlin dialect, «Berlinerisch,» is generally frowned upon. If you use it, intentionally or unintentionally, you get socially degraded and labeled as uneducated. Berlinerisch is the language of the gutters and backyards. That’s how taxi drivers talk or sausage sellers, the poor and the losers who have nothing to say except their names in the welfare offices. The Nazis used it as their brand voice. People who have something to say don’t use it, people with a university degree, a stock portfolio, a decent job.

A particularly rough variant is spoken in Brandenburg (the federal state surrounding Berlin). Even Urberliners find it disgusting, especially those who have climbed the social ladder. You meet people in Berlin who were born here but speak such flawless, sterile Standard German that they might as well have been born somewhere else. Nothing reminds you of the rough melody of the streets of their childhood anymore.

You don’t learn to speak Berlinerisch at school or at home, but casually in the street, with your playmates and on public transport. Parents who want to do something good for their children forbid them to speak this dialect. Don’t play with the muckrakers, don’t sing their songs and above all don’t use their language! Once you start speaking Berlinerisch, it takes years of dedication to get rid of the slang.

An educated person would only speak the Berlin dialect for fun, «out of mischief,» complained Hans Meyer more than a hundred years ago in his book «Der richtige Berliner» («The Real Berliner»). Meyer was an Urberliner, and he was angry about how sloppy most newcomers were with the Berlin city language. He saw his beloved Berlin dialect going to the dogs.

The Wall divided Berlin not only ideologically, economically, and mentally but also linguistically: West Berliners speak the purest standard German. If they have an accent at all, it’s a Swabian one. In West Berlin, city slang has given way to either village dialect or standard German. Only those at the bottom, in Wedding and Neukölln, speak with a Berlin accent. And in the East.

In East Berlin, all classes, educated and uneducated, adopted the Berlin dialect. The construction worker spoke with the same accent as the sculptor, the professor, the road builder, the actress, and the shop assistant. The only difference was in the grammar: for all their solidarity with the heroes of labor, the intellectuals did not refrain from using it correctly.

Speaking the Berlin dialect was as state-supporting as it was subversive. State-supporting because the dictatorship of the proletariat was the goal of the state. The vernacular of the common people was, therefore, respected. But the comrades didn’t really like the pictorial, practical idiom. Faced with the sad reality of socialism, they preferred to take refuge in the abstract. After all, they were up-and-comers and wanted to be something better. They were suspicious of the language of ordinary people. But they couldn’t silence the ruling class, at least as far as the dialect was concerned. There were worse things that had to be prevented.

East Berlin was ruled almost exclusively by Saxons. From the first head of state, Walter Ulbricht, who lisped like a eunuch, to the party secretaries who taught the Berliners about true socialism—almost everyone had a Saxon accent. East Berliners resisted the Saxon invasion by emphasizing their Berlin accent. And thus it had a subversive effect. It was the rebellion of sobriety against hollow phrases, the triumph of reality over whitewashing, a linguistic protest against the bigwigs from Saxony.

The growing together of the city might have been easier if more people in the West had spoken the Berlin dialect. After the fall of the Wall, people were disappointed by the language barriers. They thought they were close to each other, yet they were strangers. In the western part of the city, people were surprised that even well-dressed East Berliners who belonged to the social upper class spoke clearly in dialect. In the eastern part of the city, people were amazed that in the west «keen Aas berlinert» («no carrion speaks Berlinerisch»).

Today, Berlinerisch has become a repository of memory, a question of identity. Speaking it signals non-conformity and loyalty to oneself. It means resisting a monotonous image of society. Not everyone can afford that. However, it will likely disappear. Because gentrification is driving out the locals. Because the big industrial companies are disappearing, and with them the working class. Because the corner pubs are also disappearing, making way for cocktail bars and coffee shops. Because of the uniformity of the bourgeoisie, which likes to speak like the newspapers it reads, i.e. as printed. And because people are ashamed of their language and see it as a particularly reprehensible characteristic of the precariat.

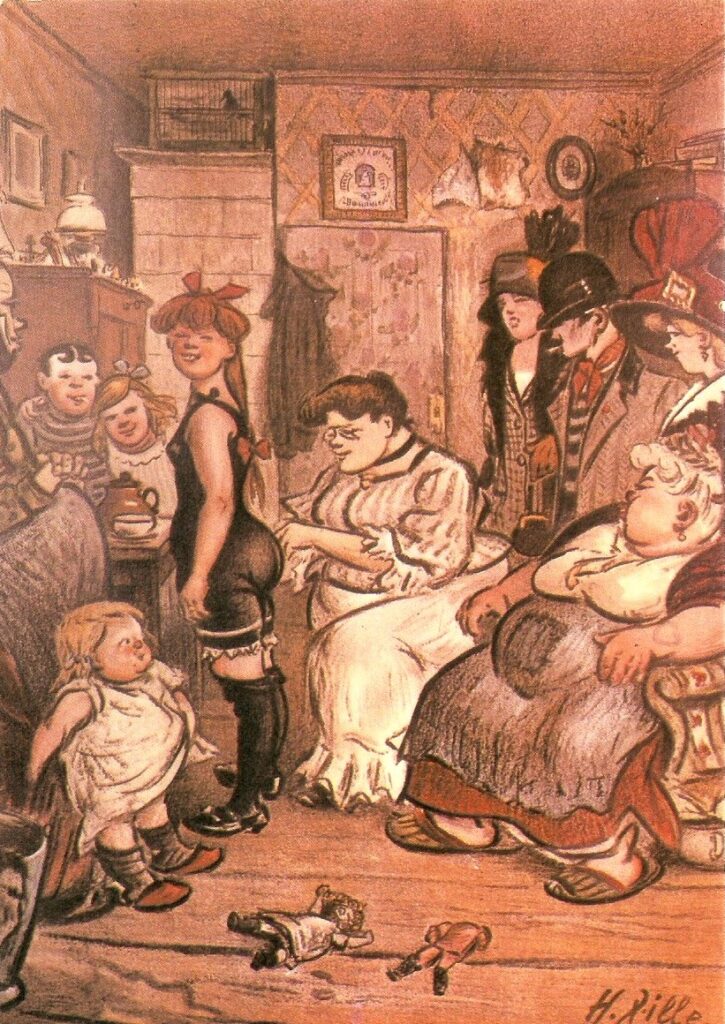

The dialect is dying—and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Everyone is crying that the Urberliner are being lost to gentrification. But what are Urberliners really? A bunch of boozers? The same blunt jokes since the factories started grinding the proles? Even Heinrich Zille, the famous Berlin caricaturist, knew: «Lower class is not cool. Proletarians are nothing to be proud of; they’re at the bottom of the food chain.» And the proletariat no longer exists anyway. Fewer and fewer people are actually working here, more and more are on benefits.

Urberlin cannot be saved. The miracle is that it has survived for so long. The fact is that the Berlin dialect, if you get it right, is actually incredibly silly and makes the speaker sound stupid. It’s not as awful as Swabian or Bavarian or Swiss German. But awful.

When they mean something very, very small, Berliners talk about an idea: «Can you please turn up the heat ‹an idea›?» Or even more precisely: a «small idea.» This predilection for the concrete is, and always has been, a Berlin peculiarity. When the Nazis seized power, the Berlin painter Max Liebermann made a famous statement: «I can’t eat as much as I want to throw up.» You can’t be more specific than that. The question is: what will replace the Berlin dialect? Who knows. But it might be a good idea to pick up some Arabic and Turkish.

You could write treatises on the Berliner Schnauze, and, in fact, people have. In other places, people might be embarrassed if others wrote a dissertation on the inferior aspects of their local dialect. The Berliners are rather proud of it. They are firmly convinced, without irony, that they speak «real German,» that everyone understands them, and that all other dialects are incomprehensible. Basically, every Berliner is right and everyone else is wrong. Only the others make mistakes—of that they have no doubt.

Expats can get by in Berlin without any knowledge of German. If you live in a migrant ghetto, too. You don’t need many German words to get through the day: «Keine Ahnung,» «Mir auch egal,» «Kannst mich mal,» «Verpiss Dich» and «Tschüß»—«I don’t know,» «I don’t care,» «Fuck you,» «Fuck off» and »Bye.» In fact, you could get through your whole life with these words. You wouldn’t need any more. If you don’t mind living in a closed-off parallel world where only English, Spanish, Hindi or some other language is spoken. This annoys the native Germans; they feel colonized.

Berlin is not only a linguistic anomaly but also a sartorial enigma. The city’s fashion sense is as perplexing as its dialect, offering a peculiar panorama of human and stylistic abysses. It’s no secret that Berliners have long been indifferent to dressing well, and any attempts to reform their fashion choices have been abandoned as futile.

Gone are the days when people would carefully select their finest attire before stepping out. Today, many seem to have forgotten to get dressed altogether, trading elegance for the comfort of baggy, functional clothing that barely passes the sniff test. The city has embraced a utilitarian approach to fashion, where practicality reigns supreme, and style is an afterthought.

In Berlin, it’s perfectly normal to stroll through the city in a stained tracksuit or run errands in patent leather platform shoes paired with pajamas. Job interviews, dinners, or even a night at the ballet? No problem—sweatpants and sneakers are considered perfectly acceptable. The city’s fashion ethos is a curious blend of irony and indifference. In the city center, you’ll find people ironically reviving nineties fashion, while in the suburbs, the same looks are worn with unironic sincerity.

Some Berliners have adopted what can only be described as «prolo-chic,» a style that mimics the clichéd appearance of the precariat but comes with a hefty price tag. Scuffed trainers, hoodies that resemble cleaning rags, ripped jeans, and shoulder bags that look like crumpled chip bags—yet cost a small fortune—are all part of the aesthetic. Tracksuits, once the domain of pimps, have become a symbol of this paradoxical fashion statement. It’s a fascinating commentary on the contradictions of our times, where people dress as if they’re part of the working poor while spending lavishly on their «distressed» looks.

«Sweatpants are a sign of defeat. You lost control of your life so you bought some sweatpants.» Karl Lagerfeld

Classic formal office attire is a rare sight on Berlin’s streets, reserved for a handful of dedicated individuals. In fact, it’s uncommon to see anyone dressed conspicuously—unless you count leopard-print leggings paired with slippers at the supermarket or orange socks with yellow jeans as conspicuous. In neighborhoods like Wedding, you’re considered overdressed if your jogging bottoms match your top. Dressing neatly can even raise suspicions—are you a manager, a banker, or, heaven forbid, a landlord?

In Friedrichshain, the uniform is black—not because it’s cool, elegant, or existentialist, but because it’s practical. Berlin is a dirty city, and black hides the stains of daily life: kebab sauce, vomit, ashes, and other urban remnants. Light-colored clothes are a liability here. The city’s fashion isn’t about style; it’s about survival. Berliners have mastered the art of dressing for the grime, embracing a look that’s as unpretentious as it is utilitarian.

In the end, Berlin fashion, like the language, is a reflection of the city’s character: raw, unpolished, and uncultivated.

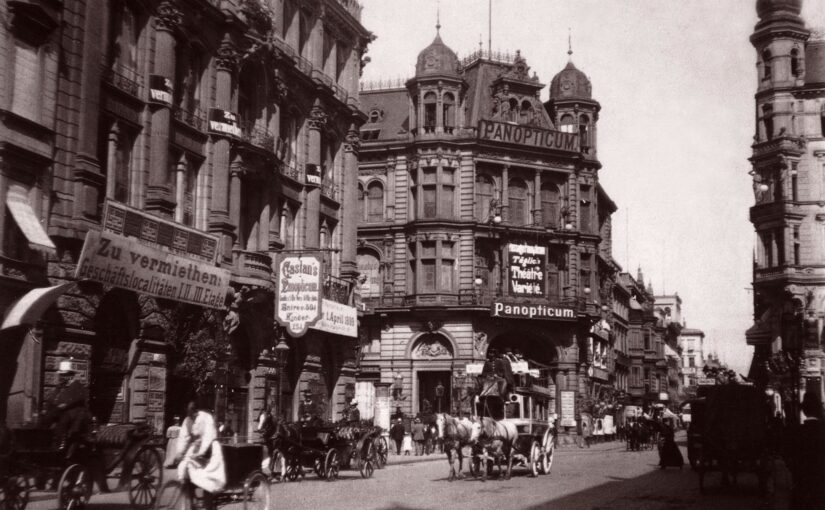

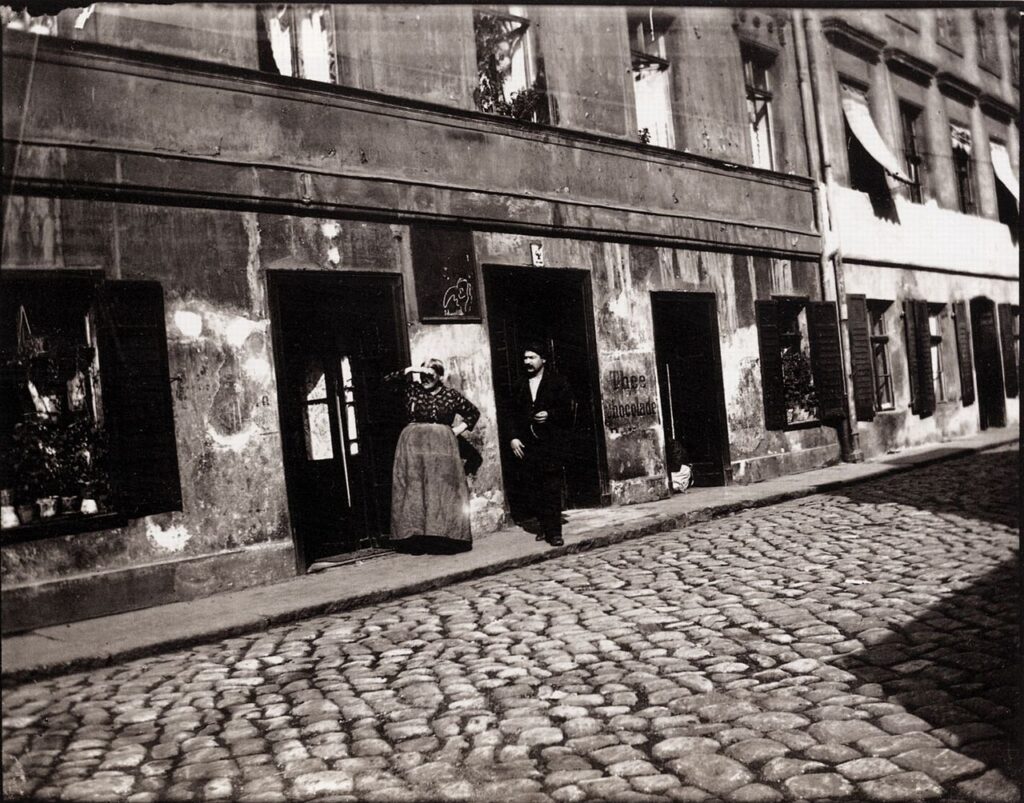

Featured image: Berlin 1900 Friedrichstrasse Heinrich Zille.