DR) enacted one of the shortest laws in German legal history. Without prior discussion, the law was rubber-stamped within minutes. It consisted of just two succinct paragraphs:

Paragraph 1:

«The Head Office for the Protection of the National Economy, previously under the Ministry of the Interior, shall be transformed into an independent Ministry for State Security. The Law of 7 October 1949 on the Provisional Government of the German Democratic Republic (Law Gazette p. 2) is amended accordingly.»

Paragraph 2:

«This act shall come into effect on the date of its promulgation.»

Thus, the Stasi was created.

The Ministry for State Security (Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, or MfS), commonly known as the Stasi, served as the secret police and intelligence service of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) for nearly four decades. Guided by Lenin’s dictum, «Trust is good. Control is better,» the SED extended its control over nearly every aspect of citizens’ lives. As the self-proclaimed ‹shield and sword of the party,› the Stasi’s primary mission was to monitor, control, persecute, and suppress perceived ‹enemies of socialism› to secure the SED’s grip on power. Like the Berlin Wall, the Stasi was a key instrument of the SED’s authoritarian rule, ensuring the party’s dominance through fear, surveillance, and repression.

Erich Mielke became the first deputy to the then Minister Wilhelm Zaisser. Mielke’s career was marked by brutality and unwavering loyalty to Stalinist ideology. In 1931, as a young communist, he and an accomplice assassinated two Berlin police officers on behalf of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). The double murderer escaped and then carried out Stalinist purges in their own ranks during the Spanish Civil War. By the summer of 1945, Mielke had returned to Berlin, where he quickly assumed a leadership role in the newly formed secret police.

Mielke was neither a gifted politician nor a master spy, and actually not even particularly bright. He felt a deep contempt for any sophistication, and combined with an extremely simplistic friend-or-foe worldview, he firmly believed that the end justifies the means. What he lacked in intelligence and education, Mielke made up for with sheer ruthlessness. His infamous tirades against his subordinates were laced with violent threats: «I’ll chop yer head off!» he would bark at them when they reported failures.

He was sneaky, paranoid, and vulgar, and when he later became head of the Stasi, he was primarily responsible for the trail of blood it left in the GDR. «All that gibberish about not executing, about not having a death sentence—it’s all bullshit, comrades,» he once said. «Execute, if necessary, without a court sentence.» His guiding principle was simple and brutal: «Don’t hesitate to attack.»

Modeled after the Soviet Cheka and later the KGB, the Stasi was tasked with eliminating opposition by any means necessary. It operated with near-total impunity, violating virtually every paragraph of the GDR’s penal code. Despite constitutional guarantees of postal secrecy, the Stasi routinely opened letters and packages without judicial authorization, photographing or copying their contents—or simply confiscating them. It tapped phones, recorded private conversations, bugged apartments, and conducted arbitrary surveillance. Informants were planted in opposition groups, churches, and even families, while fabricated evidence and false reports were used to justify arrests and prosecutions.

«Comrades, we must know everything,» was Mielke’s mantra. Everyone—without exception—was a potential target for preemptive surveillance. Because anyone, even the most reliable citizen, could fall prey to the temptations of the enemy. Any form of deviant behavior, or what the Stasi termed ‹hostile-negative behavior,› had to be identified and neutralized as early as possible.

Even without the aid of modern technology, surveillance was pervasive, extending deep into the private lives of citizens. The regime sought to know everything: public sentiments, ideological doubts, ‹hostile› opinions, contacts with the West, perceived immoral behavior—whatever it deemed worthy of scrutiny.

Few truly understood the full scope of the Stasi’s reach. Though its presence was felt everywhere, it remained largely invisible. There was no place where people didn’t suspect they were being watched, no one they didn’t fear might be an informant. Stirring this atmosphere of paranoia was, in fact, part of the Stasi’s cynical strategy. «We had lived like behind glass», wrote the novelist Stefan Heym, «like pinned beetles, and every wriggling of the legs had been noticed with interest and commented on in detail.»

The Stasi’s elaborate apparatus of repression relied on blackmail, coercion, and psychological manipulation to force compliance. Those who criticized the regime or sought to leave the country faced imprisonment, ruined careers, or even official child removal. The Stasi’s methods included defamation, intimidation, and even human trafficking and murder, particularly at the border.

The Stasi’s reach extended beyond East Germany. Commandos kidnapped hundreds of individuals from the West, including Western agents, renegades from their own ranks, and critics of the regime. Some, like former police chief Robert Bialek, did not survive their abduction. Others, such as Paul Rebenstock and Sylvester Murau, were executed after sham trials. The Stasi also carried out direct assassinations. Wolfgang Welsch, a former political prisoner who later helped people escape to the West, survived three assassination attempts, including a car bombing, a sniper attack, and thallium poisoning. Others, like Swiss refugee helper Hans Lenzlinger and West German activist Kay Mierendorff, were less fortunate—Lenzlinger was shot dead, while Mierendorff was permanently disabled by a letter bomb. In 1976, refugee helper Michael Gartenschläger was ambushed and killed by a Stasi commando near the inner-German border.

The Stasi’s tactics were ruthlessly effective. It destroyed reputations, careers, and families through psychological pressure, fabricated evidence, and smear campaigns. Targets were subjected to professional sabotage, restricted movement, revoked licenses, and relentless surveillance. The Stasi spread rumors of adultery, alcoholism, and other scandals, often targeting family members to deepen the psychological toll. Its operations created an atmosphere of mistrust that permeated every level of society, turning friends and relatives against one another.

The Stasi was not restricted to surveillance, but had executive powers and could make arrests itself without oversight. It presumed to have almost unlimited police powers, threatening even when it was obviously in the wrong, because it knew it always had the upper hand. The mere suspicion of political misconduct or of actions that were interpreted by the Stasi as politically motivated crimes was enough to become a ‹target› for repressive measures.

It maintained 17 detention centers where suspects were interrogated, often for days, using psychological and physical torture to extract confessions. Between 1952 and 1988, the Stasi initiated investigations against 110,000 people for offenses such as ‹anti-state agitation,› ‹unauthorized border crossing,› and ‹crimes against the state.› Most cases resulted in convictions, with judges relying solely on Stasi files rather than witness testimony or defense arguments.

The Stasi’s impact on East German society was profound and devastating. It shattered millions of lives, destroyed families, and crushed dissent through a combination of psychological terror and brute force.

Despite the country’s dire economic conditions, the Stasi was allocated a budget of 4.2 billion East marks. It owned over 2,000 apartments and buildings, primarily for surveillance purposes, but also for recreational facilities specifically designed for its employees. In addition, the Stasi had to supply its personnel with weapons, surveillance equipment, and other resources. A significant portion of this budget was devoted to covering the immense personnel costs.

At its peak, the Stasi employed 85,000 to 91,000 full-time staff across 26 departments, plus its own university in Potsdam, a secret workshop for spy technology—the ‹Operative Technical Sector› OTS and the paramilitary unit, the ‹Feliks Dzierzynski› guard regiment with 11,000 soldiers. It also relied heavily on unofficial collaborators, who snitched on colleagues, friends, classmates, and even family members. In total, 189,000 unofficial informants (Inoffizielle Mitarbeiter, or IMs) collaborated with the Stasi.

The Stasi went to great lengths to recruit individuals willing to betray their fellow citizens. They didn’t just assess the candidates themselves, but also scrutinized their entire environment, gathering detailed information to determine where each recruit could be most useful. Doctors and psychologists were enlisted not only to evaluate the candidates’ suitability but also to uncover any vulnerabilities that could be exploited.

If a Stasi officer and his superior deemed a potential recruit promising, the candidate was required to sign a handwritten loyalty pledge. Depending on the circumstances, signatures were obtained through a mix of persuasion, bribes, or—more commonly—coercion. The pressure could range from subtle intimidation to overt threats, including the possibility of travel or study bans, public defamation of the recruit or their family, or the offer to overlook real or fabricated offenses.

Even serious crimes, such as child abuse, were overlooked if the individual agreed to collaborate with the Stasi. But the most valued recruits were those who volunteered out of ideological conviction. These individuals were often the most reliable, and the Stasi made sure to keep them loyal by occasionally rewarding them with liquor, cigarettes, cash bonuses, or even travel privileges. While some collaborated out of fear or careerism, only a few had the courage to refuse the Stasi’s demands.

To enforce Prussian discipline within its own ranks, the Stasi monitored its employees more than any other population group. Every aspect of their lives—family relationships, hobbies, and choice of partners—was scrutinized. The Stasi showed no mercy to those it deemed renegades, whether real or suspected, within its own ranks.

Werner Teske, a Stasi officer, had briefly entertained the idea of defecting to the West but had never taken concrete steps toward it. Although the GDR’s harsh penal code mandated the death penalty only for actual acts of serious treason—which Teske had not committed—he was executed by a gunshot to the neck in Leipzig prison in 1981. His execution was not just a punishment, but a brutal act of revenge and a chilling example meant to deter anyone else from considering defection.

From the 1980s onward, the Stasi faced significant personnel shortages. Recruitment of voluntary cadres became increasingly difficult, prompting the regime to turn its attention to the country’s youth, actively seeking and grooming ‹suitable candidates.› In 1989 alone, it’s reported that about 1,300 children worked for the Stasi, with the youngest being just 12 years old. To maximize control and indoctrination, it was especially advantageous to target children with no family ties, making them easier to isolate and manipulate. They also reportedly recruited children of parents who had defected to the West.

In 1979, Mielke expressed the Stasi’s goal for these young recruits: «You must find young Chekists, identify them, and train them so thoroughly that you tell them, ‹You go there, you shoot him in enemy territory. You go there, and even if they catch you, you stand before the judge and say, ‹Yes, I killed him on behalf of my proletarian honor!›› That’s how it must be. The mission must be carried out, even if you’re destroyed in the process.»

The Stasi’s crimes were the inhumane consequence of the Marxist-Leninist ideology’s claim to absolute truth. Over time, the promise of communism—creating a classless, egalitarian society—had proven hollow. The ‹new socialist man› had not emerged. Instead, the mass of the population suffered from deprivation and psychological traumatization. Alcohol consumption was high, as were suicide and imprisonment rates, mental illness was rampant, as was absenteeism from work. Meanwhile, a small elite of party functionaries reaped the rewards, living lives of luxury far removed from the struggles of ordinary citizens.

Though the regime frequently invoked the teachings of Marx and Engels, it ignored Marx’s prescient warning about the ‹explosive power of democratic ideas› and the inherent human drive toward freedom. The system was bound to fail because it could not reconcile its own contradictions.

By the 1980s, the centrally planned economies of the Eastern Bloc had become increasingly inefficient. State-run industries were often outdated, unproductive, and wasteful, while the lack of competition, innovation, and consumer choice led to widespread economic stagnation. Basic goods and services were in short supply, and many citizens in Eastern Europe endured poor living standards compared to their counterparts in the West. Even the Soviet Union, under Mikhail Gorbachev’s leadership, was struggling to sustain its own economy.

Gorbachev made it clear that the Soviet Union would no longer use military force to maintain control over its satellite states. In 1989, during a speech at the United Nations, he declared that the Soviet Union would no longer intervene in the internal affairs of Eastern European countries, effectively ending the Brezhnev Doctrine. This policy had previously justified the suppression of uprisings in Hungary (1956), Czechoslovakia (1968), and Poland (1980s). Gorbachev’s shift in policy gave Eastern Bloc countries the breathing room to pursue their own reforms and challenge Soviet control.

In Poland, the Solidarity movement, led by Lech Wałęsa, had been a formidable force of resistance to Communist rule since the early 1980s. In 1989, following negotiations between the Communist government and Solidarity, semi-free elections were held. Solidarity won a decisive victory, forcing the Communist regime to negotiate a peaceful transition of power. This landmark event signaled to the rest of Eastern Europe that meaningful change was possible without the need for violent uprisings.

In the GDR, the movement of refugees and emigrants played a pivotal role in the collapse of the regime. Since May 1989, thousands of people had fled across the border from Hungary to Austria, while others fought to escape the country by occupying West German embassies in Budapest, Prague, and Warsaw. The pressure on the SED steadily mounted. At the same time, late summer and autumn saw growing demonstrations in the GDR calling for democracy and the freedom to travel. It became increasingly clear that the end of the German Democratic Republic was imminent, and by November 1989, events unfolded rapidly.

On November 4, the largest mass demonstration in the country’s history took place at Alexanderplatz in Berlin, organized by artists. Hundreds of thousands of people participated, and the event was broadcast live on television—a first in the GDR. Several prominent artists and civil rights activists gave speeches, openly criticizing the regime, much to the crowd’s approval. Several SED politicians also took the stage, including Politburo member Günther Schabowski and former Stasi officer Markus Wolf. When Wolf spoke of a ‹renewed socialism› and acknowledged his 33 years as a Stasi general, he was met with boos from the crowd. It was at that moment, as he later recounted in interviews, that he realized, «it was over.»

Finally, on November 9, Schabowski unintentionally dealt the regime the final blow in front of running television cameras. For weeks, the state leadership had been desperately searching for a solution to the growing refugee and travel crisis. Egon Krenz, the newly appointed leader, ultimately decided to allow those wishing to leave the country permanently to cross through all border points to the Federal Republic and West Berlin. The authorities anticipated a massive wave of emigrants, potentially numbering in the hundreds of thousands, but they believed they could manage the loss without destabilizing the regime.

This arrangement was to take effect the following day and was meant to be temporary until a final travel law could be passed. The goal was to relieve the pressure on the regime, rid themselves of dissidents and potential troublemakers, and, behind the scenes, eventually reimpose travel restrictions. Krenz wanted the decision to be publicly announced that same evening. The police authorities responsible for issuing passports were notified by 6:00 p.m. to prepare for the anticipated rush the next morning. Meanwhile, Schabowski was holding a press conference, where he was handed a note with the decision, which he read aloud.

When a journalist asked when the regulation would come into effect, Schabowski, unsure of the details, stammered that, to his knowledge, it was effective immediately. From his point of view, it was probably a pointless question, because the decisions of the Politburo always applied immediately—why else would they be announced? While Schabowski may not have fully grasped the consequences of his words, the journalists immediately understood the implications and reported that the borders were now open.

When East Berliners heard the news, they took their leaders at their word and rushed to the border crossings. Peaceful citizens, confronted by armed border guards, were unsure of what would happen next. But when people tentatively lifted the first barrier and entered the border facilities, the border guards did nothing. The wall had fallen. It wasn’t a party bureaucrat or a border guard who brought it down—it was the people. The fall of the ‹anti-fascist protective wall› marked the beginning of the dissolution of the GDR.

In hindsight, it’s hard to believe the regime managed to last as long as it did. The Stasi, relying on the reports of its vast network of informants, had a surprisingly accurate grasp of the political situation. Since the uprisings of June 17, 1953, all Stasi offices had been required to regularly brief the leadership on the mood of the population. One such report noted: «The mood in the capital is characterized by deep disappointment, bitterness, and concern.»

After the opening of the border, the mood among MfS employees shifted drastically, marked by a deep sense of helplessness, frustration, and demoralization. As the legitimacy of the SED and its state structures crumbled, a power vacuum emerged, leaving the Stasi unable to fulfill its core mission of maintaining internal control. Preoccupied with itself, the party leadership watched idly. By the end of December, the ruling party was in a state of disintegration, having lost nearly 900,000 members.

On November 6, Erich Mielke issued an order to «reduce the stock of official regulations and directives in the district offices/property offices» and to move files to the district administrations, which were to be better protected. Ultimately, this instruction resulted in a wave of file destruction, which was implemented inconsistently in the chaos that ensued in the individual offices. To this day, it is not clear how much material was burned, shredded, or torn apart. Over the following months, further, sometimes contradictory instructions led to additional file destruction.

The MfS fragmented internally. Central directives were interpreted and implemented differently; the offices in the districts and counties waited in vain for an overarching concept and a clear strategy from the headquarters in East Berlin. The strict top-down hierarchy of command no longer applied. The loss of legitimacy of the socialist ideology and the associated loss of a clear ‹enemy image,› which the Stasi had internalized and held together for 40 years, became increasingly noticeable.

Its internal crisis came to a head with a speech by Erich Mielke to the People’s Chamber on November 13. With his attempts to justify the surveillance of the population, the minister, who had resigned a few days earlier, presented such a disastrous picture that many employees distanced themselves from him.

Around November 20, a spontaneous demonstration erupted in the courtyard of the HV A (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung, the foreign intelligence branch of the Stasi) building, involving approximately 100 to 150 employees, predominantly younger staff. This marked a historic moment: for the first time in the history of the MfS, employees had organized a protest directed against their own leadership and the sluggish pace of reform within the organization.

Employees complained that in the past they had drawn attention to many problems, shortcomings and mismanagement and had even made suggestions for improvement—but nothing had happened. The demonstration did not achieve much. But it did exert considerable influence and pressure on other service units, where similar tendencies became apparent. And it led to another, much larger protest action by around 1,000 employees of the Stasi headquarters—this time directly in front of the main building of the Ministry of State Security.

The continued existence of the Stasi was increasingly questioned. For Hans Modrow, the new head of government, the focus shifted to saving the state itself. The Stasi, once the bedrock of internal security, was now a destabilizing force. To the general population, it had become synonymous with oppression, persecution, and surveillance. Its fall from grace fueled resentment within its own ranks, as many saw the Stasi as now being responsible for the party’s failures.

Starting in December 1989, Stasi offices across the GDR were occupied peacefully by demonstrators. The first occupation occurred on December 4 in Erfurt, led by a group of determined women, and quickly spread to other cities. The demonstrators demanded an end to the destruction of Stasi files and called for proper oversight. Fears began to rise among the public that the destruction of documents would erase evidence of the regime’s abuses, human rights violations, and surveillance practices. As occupations spread, the pressure on the government intensified.

The final dismantling of the Stasi was formally decided during the Round Table talks in mid-January 1990, a series of negotiations between the East German government, opposition groups, and civil rights activists. However, the symbolic end of the feared Ministry for State Security came on January 15, 1990, when tens of thousands of enraged citizens gathered in front of the Stasi headquarters in Berlin-Lichtenberg and finally stormed the premises.

They dragged furniture out of the offices, rummaged through financial records, and even placed a noose around the neck of a Stasi officer. Meanwhile, without them noticing, in the most secluded rooms of the building, a desperate last-ditch effort was underway to destroy evidence: a hundred file shredders in the most remote rooms were relentlessly fed with sensitive documents. By the end, only two shredders—an American and a Japanese model—were still functioning; the rest had burned out from overuse.

Some of the documents that had not yet been destroyed fell into the hands of the infuriated people and have since disappeared. The HV A had already disposed of almost all of its documents by the fall of 1989. However, individual files ended up with foreign intelligence services, such as the so-called ‹Rosenholz› file, which the American secret service CIA is said to have acquired from Russian intelligence circles.

The SED regime had been stripped of its power once and for all. On February 8, 1990, the Modrow administration officially ordered the dissolution of the Stasi—precisely 40 years to the day since its founding. With the decision made that no successor organization would take its place, many MfS employees began receiving their dismissal papers starting in February 1990. In some cases, their departure was accompanied by one last round of ‹legend-building› in their job references—rebranded as former employees of customs, the People’s Police, or bodyguards working under the Ministry of the Interior. Some were awarded the dubious honor of being described as having been «committed to the debate.» By June 30, 1990, the Ministry for State Security effectively ceased to exist.

The Stasi files tell a story of deceit and betrayal on a national scale: husbands spying on their wives, children on their parents and priests on their parishioners.

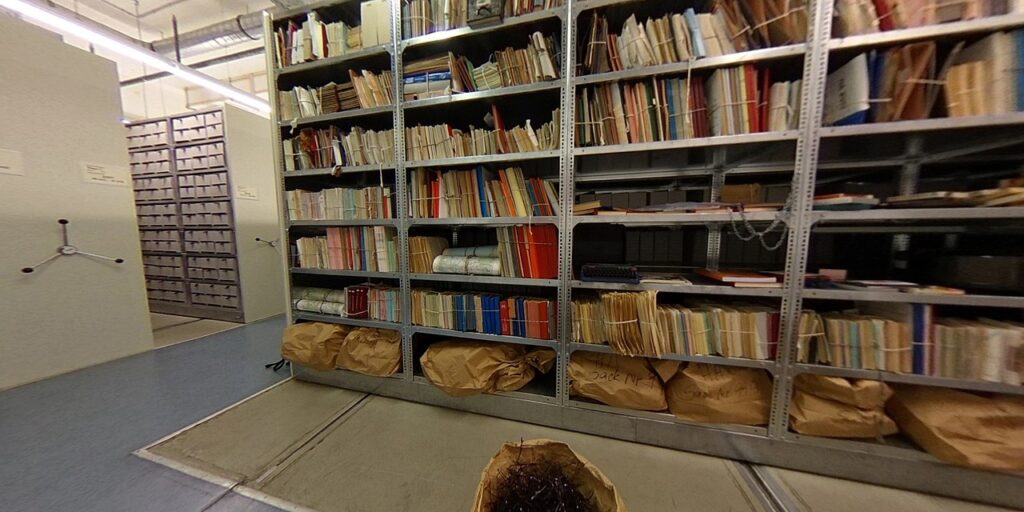

In September 1990, GDR civil rights activists once again occupied the Stasi archive and launched a hunger strike, demanding the preservation and long-term accessibility of the Stasi files. Their efforts were successful. An additional protocol to the German-German Unification Treaty mandated the institutional processing of these files. All Stasi documents retained from the GDR were to be stored in an archive that officially opened on January 2, 1992. The archive now holds over 111 kilometers of files, 46.7 million index cards, and more than 2 million photos. It also contains nearly 15,000 sacks of shredded files files that the MfS had intended to incinerate in 1989.

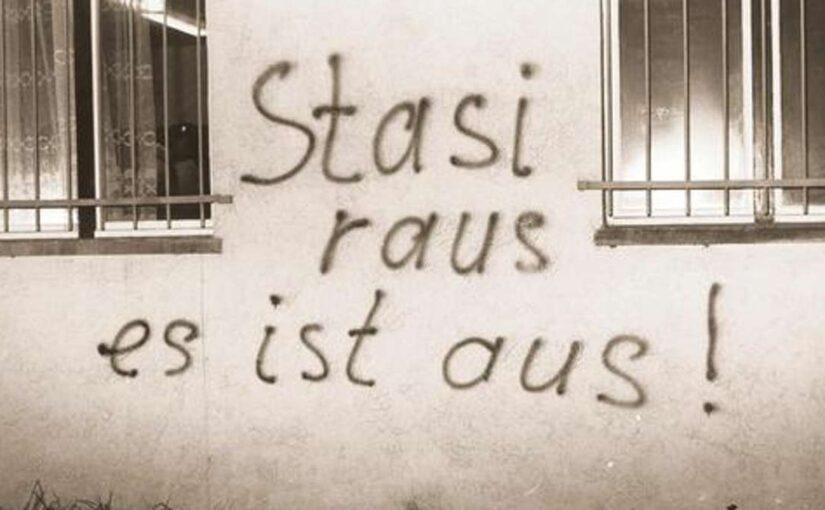

Featured image: «Stasi out» slogan on the outside wall of the Suhl Stasi headquarters on December 5, 1989, after demonstrators stormed the premises. (© Reinhard Wenzel).