«Let justice be done, though the world perish.»—Historical Habsburg Motto

A modest noble house from a rugged alpine valley began as loyal vassals, managing estates with shrewd care. Marriages wove their blood into greater lines, securing lands from misty forests to sunlit plains. Castles rose under their banners, each stone laid with calculated ambition. By the time a golden crown rested on their patriarch’s head, their domains sprawled across rivers and mountains, knit by pacts and dowries. Cathedrals bore their crests, and their court buzzed with envoys from distant realms. Armies marched at their command, while their children, wed to foreign thrones, carried their influence like seeds on the wind. Palaces gleamed, filled with tapestries of their triumphs, as their name became a whisper of power in every corner of the continent.

The Habsburgs, one of Europe’s most enduring and formidable dynasties, wielded unparalleled influence over Central and Eastern Europe for nearly seven centuries. The dynasty’s ascent began in earnest with Rudolf I, a cunning and determined noble who secured the German kingship in 1273 after defeating his rival, Ottokar II of Bohemia, in the Battle of Dürnkrut. This victory not only granted Rudolf the Austrian duchies but also marked the Habsburgs’ entry into the upper echelons of European power. Over the subsequent centuries, the family expanded its reach, leveraging both battlefield triumphs and the imperial electoral system of the Holy Roman Empire. By 1452, their influence crystallized when Frederick III, a patient and relentless ruler, was crowned Holy Roman Emperor. His coronation established a near-unbroken Habsburg grip on the imperial throne that endured until the empire’s dissolution in 1806, cementing their status as a dynastic juggernaut.

Under Frederick III, the Habsburgs boldly proclaimed their imperial vision with the cryptic motto A.E.I.O.U., Alles Erdreich ist Österreich untertan (All the world is subject to Austria) or Austriae est imperare orbi universo (Austria is destined to rule the world). These words captured their ambition for global dominance, reflecting the dynasty’s unyielding drive for power and influence.

Rather than relying solely on conquest, the Habsburgs famously adhered to the motto «Bella gerant alii, tu felix Austria nube», «Let others wage war; you, fortunate Austria, marry.» This approach bore spectacular fruit. The marriage of Maximilian I to Mary of Burgundy in 1477, for instance, brought the opulent Burgundian Netherlands, rich in trade and culture, into the Habsburg fold, laying the groundwork for further expansion.

Maximilian’s grandson, Charles V (1500–1558), epitomized the dynasty’s apex. Born into a web of inheritances, Charles ruled an empire that spanned Austria, Spain, the Low Countries, southern Italy, and vast colonial territories in the Americas. His reign saw the Habsburgs become a global superpower, though the sheer scale of his domains also strained their ability to govern effectively.

By the 18th century, the Habsburgs had solidified their rule over the Austrian Empire, a formidable entity that emerged as a linchpin of European geopolitics. The reign of Maria Theresa (1717–1780), one of the dynasty’s most enlightened and resolute rulers, exemplified their adaptability. Ascending the throne in 1740 amid the War of the Austrian Succession, a brutal conflict sparked by challenges to her legitimacy, she defied expectations by preserving her inheritance. Maria Theresa introduced sweeping reforms: she modernized the military, centralized the administration, bolstered the economy through agricultural innovation, and championed education by mandating schooling for children. Her son, Joseph II, continued her legacy of reform, though his radical policies often provoked resistance.

The Habsburgs’ influence persisted into the 19th and early 20th centuries, most notably under Emperor Franz Joseph I (1830– 1916), whose 68-year reign remains one of the longest in European history. Ascending the throne in 1848 amid revolutionary upheaval, Franz Joseph faced the daunting task of holding together an empire fractured by ethnic diversity and nationalist fervor. His realm encompassed Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Croats, Serbs, Italians, and more, a vibrant but volatile mosaic of cultures and languages. The 1867 Austro-Hungarian Compromise, a landmark agreement born of necessity, transformed the empire into the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. This arrangement granted Hungary equal status with Austria, with its own parliament and prime minister, while Franz Joseph retained authority over foreign policy and the military. Though intended to stabilize the empire, the compromise inflamed tensions among other ethnic groups, particularly the Slavs, who felt sidelined by the dual structure.

Franz Joseph’s reign was marked by both grandeur and tragedy. The glittering Viennese court, a hub of art, music, and intellectual life, masked an empire in decline. The rise of nationalist movements, especially among Hungarians and Slavs, challenged Habsburg authority, while external powers like Prussia and Russia encroached on its influence. The assassination of Franz Joseph’s nephew and heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, proved the fatal spark that unraveled the dynasty and ignited a global catastrophe.

Franz Ferdinand was a complex figure: a man of rigid posture, his mustache impeccably trimmed, who stood tall in a tailored uniform adorned with gleaming medals. His sharp eyes, beneath a furrowed brow, surveyed rooms with a mix of authority and unease. He spoke in clipped tones, favoring talk of hunting or military drills, yet his hands fidgeted with a pocket watch when conversations turned to politics. Maps and ledgers cluttered his desk, where he’d sit late, tracing borders with a restless finger.

On horseback, he cut a commanding figure, barking orders to soldiers, but in quiet moments, he’d pause to watch birds soar, a faint softness breaking through his stern demeanor. A reformist at heart, he envisioned a restructured empire under «trialism,» granting greater autonomy to the Slavic peoples alongside Austria and Hungary. Yet his ideas alienated both Hungarian nationalists, who feared losing their privileged status, and Slavic radicals, who demanded full independence.

When Franz Ferdinand fell deeply in love with Countess Sophie Chotek, the match sent ripples of disapproval through the gilded halls of Vienna’s imperial court. Sophie, though charming and well-bred, hailed from a minor Bohemian noble family of diminished means, a stark contrast to the lofty lineage expected for a Habsburg consort. Their union, formalized in a modest ceremony on July 1, 1900, defied convention and exacted a steep price. Franz Ferdinand, bowing to the rigid dynastic laws enforced by Emperor Franz Joseph, was compelled to renounce his three children’s rights to the throne. The couple’s offspring, Sophie, Maximilian, and Ernst, were barred from bearing the Habsburg name, instead adopting the title «von Hohenberg» in 1909. This morganatic marriage cast a shadow over Franz Ferdinand’s imperial ambitions, yet the couple forged a private life of quiet contentment, insulated from the court’s disdain.

Their sanctuary was Konopiště Castle, a romantic medieval fortress in Central Bohemia that Franz Ferdinand had purchased in 1887. Nestled amid rolling forests and serene lakes, the estate became a haven for the family. Franz Ferdinand lavished attention on the property, transforming it into a showcase of his passions: its armory brimmed with thousands of hunting trophies, its gardens bloomed with rare roses, and its halls echoed with the laughter of his children. For a time, this idyllic retreat shielded them from the political storms brewing beyond its walls.

On June 28, 1914, the Archduke and his wife arrived in Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital. The visit served multiple purposes: as Inspector General of the Empire’s armed forces, he reviewed military maneuvers in Bosnia; he inaugurated a new State Museum to strengthen Austro-Hungarian cultural and political influence in Bosnia-Herzegovina; and he quietly marked his 14th wedding anniversary with Sophie. Her non-royal status restricted their joint appearances in Vienna’s rigid court, but Sarajevo’s relaxed protocols granted them a rare public moment together. The assassination that followed unfolded in disorder.

Six conspirators lined the motorcade’s route through the city. Four hesitated as the procession passed, but two acted, executing their deadly plan. The first attack with a bomb failed, the second with a pistol killed Franz Ferdinand and his wife.

Bosnia and Herzegovina, annexed by Austria-Hungary in 1908, had become a flashpoint for Slavic resentment, and Franz Ferdinand’s visit, ostensibly to inspect troops, stoked the ire of nationalists who saw Habsburg rule as an oppressive yoke. It was Sunday, June 28, a date freighted with symbolism for Serbs: St. Vitus’ Day, commemorating the 1389 Battle of Kosovo, where the Ottoman Empire crushed Serbian forces on the «Blackbird’s Field.» The anniversary fueled a potent mix of mourning and defiance, amplifying the stakes of the Archduke’s presence.

The attack was no spontaneous outburst but the culmination of a meticulously orchestrated plot by the Black Hand, a shadowy Serbian nationalist society bent on liberating South Slavs from Habsburg dominion. Led by Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević, known as «Apis,» the group had coalesced in 1911 with a mission to forge a Greater Serbia through violence and subversion. Apis, a charismatic and ruthless figure in Serbia’s military intelligence, saw Franz Ferdinand, a proponent of reforming the empire to include Slavic autonomy, as a paradoxical threat: a reformer whose plans might stabilize Habsburg rule rather than dismantle it. The Black Hand recruited and armed a cell of young Bosnian Serbs, including the wiry, intense 19-year-old Gavrilo Princip, whose zeal for the cause burned with quiet ferocity. Smuggling pistols, grenades, and cyanide capsules across borders, the conspirators relied on a web of sympathizers to evade Austro- Hungarian authorities.

The morning unfolded with deceptive calm. At 8 a.m., Franz Ferdinand and Sophie breakfasted at the Hotel Bosna in Ilidža, a spa town ten kilometers west of Sarajevo. Over coffee and pastries, the Archduke dictated a telegram to his 12-year-old daughter, Sophie: «Mummy and I are doing very well. Weather warm and fine. We had a big dinner yesterday and a big reception in Sarajevo this morning. Another big dinner this afternoon, then departure. Give you a big hug. Tuesday. Papi.» The message, dashed off with paternal warmth, was dispatched with priority, a fleeting snapshot of normalcy. Meanwhile, in Sarajevo, the Black Hand’s operatives gathered at Vlajnić’s pastry shop. Five Bosnian Serbs and one Muslim youth collected their weapons from Miško Jovanović, a local contact, plotting their ambush along the Appel Quay, the riverside boulevard where the Archduke’s motorcade would pass. Each conspirator clutched a cyanide capsule, a grim pact to die rather than face capture.

By 9 a.m., Franz Ferdinand and Sophie attended a brief Mass at a Catholic church in Ilidža, a 20-minute interlude squeezed into a packed itinerary. At the same moment, Princip parted from a school friend, the son of Sarajevo’s public prosecutor, after a casual stroll, masking his lethal intent. He made his way to the Appel Quay, stationing himself outside Moritz Schiller’s delicatessen among a growing crowd of onlookers. Nearby, chauffeurs at Sarajevo’s main barracks readied a convoy of seven cars, debating whether the Archduke would ride in Count Franz Harrach’s open-top Gräf & Stift Phaeton (license plate A III-118) or Count Alexander Boos-Waldeck’s American limousine, its glass partition offering a veneer of protection. A last-minute delay, Franz Ferdinand opted to walk to Ilidža’s train station rather than ride, pushed their departure to 9:42 a.m., when the couple boarded a special train for the short journey to Sarajevo.

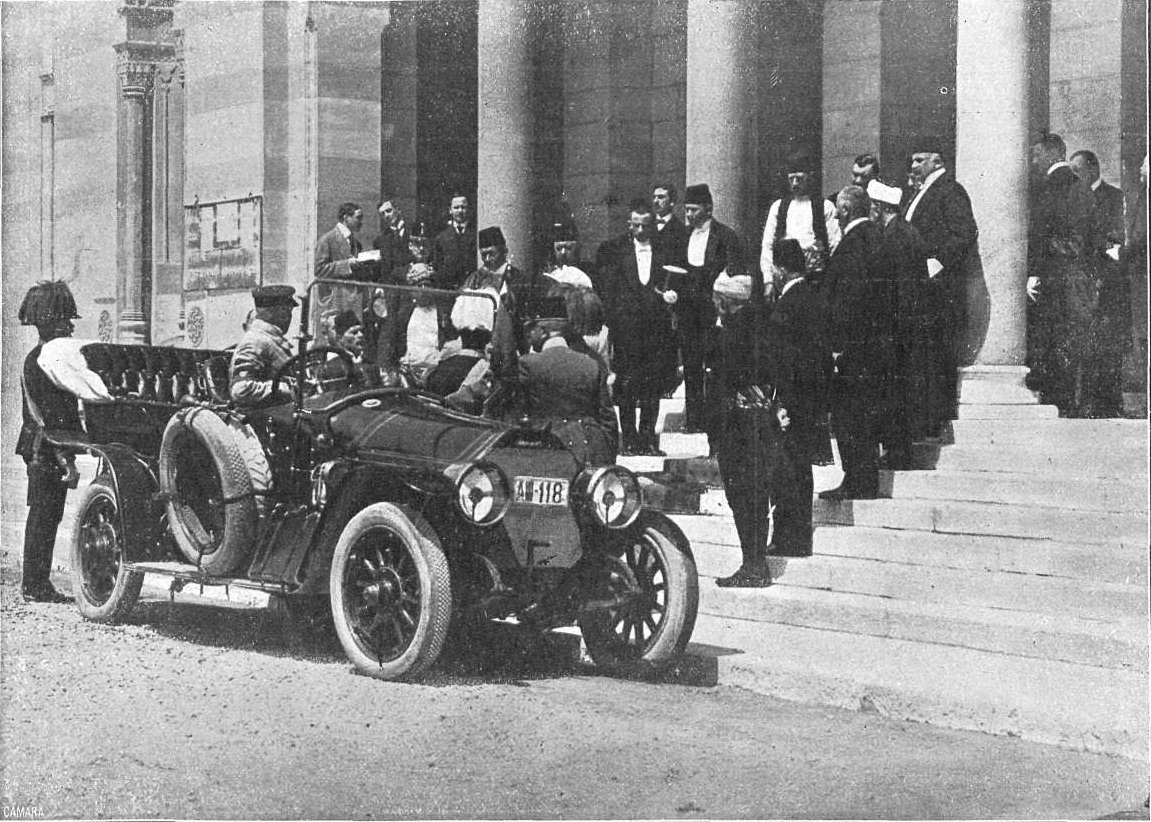

The Archduke and Sophie arrived 17 minutes late, greeted by the clang of barracks life at the city’s defensive camp. After a cursory inspection, they chose Harrach’s Phaeton for the day’s procession, a sleek convertible that left them exposed under the midday sun. Franz Ferdinand, resplendent in a mid-blue general’s uniform with a green-plumed helmet, stood out sharply beside Sophie, elegant in a white dress and wide-brimmed hat.

The moment when the Archduke of Austria arrives at the town hall after the first failed attack, where they are met by the mayor and the town council.

At 10:15 a.m., the convoy rolled through Sarajevo’s festooned streets at a leisurely ten kilometers per hour. «Please, chauffeur, slow down,» Franz Ferdinand urged Leopold Lojka, his driver, eager to absorb the city’s sights. The first assassin, Muhamed Mehmedbašić, faltered at the Čumurija Bridge, his grenade unthrown after a bystander jostled him. Moments later, Nedeljko Čabrinović seized his chance. Stationed opposite the teacher training college, he lobbed a grenade toward the Phaeton. Lojka, spotting the projectile, gunned the engine. The bomb glanced off the car’s folded roof, exploding under the next vehicle, Boos- Waldeck’s limousine, shredding its undercarriage and wounding several officers, including Colonel Erik von Merizzi. A 16- centimeter crater scarred the road as Čabrinović swallowed his cyanide and leapt into the Miljacka River, only to land on its shallow bank, retching from the ineffective poison as police swarmed him.

Franz Ferdinand, visibly shaken but resolute, halted the procession to check on the injured and ensure that aid was provided before continuing. Ignoring pleas to abandon the visit, he pressed on to the town hall, where Sarajevo’s mayor, Fehim Effendi Čurčić, welcomed him with a rehearsed speech. The Archduke cut him off, his voice taut with indignation: «You come to Sarajevo to visit, and they hurl bombs at you, it’s outrageous!» Inside, he delivered a terse address, sardonically noting the crowd’s «jubilant ovation» as proof of their relief at the failed attempt. «In our circumstances», he muttered to an aide, «the assassin will probably get a medal.» Another recalled his grim jest: «I wouldn’t be surprised if we get a few more bullets today.» Disillusioned, Franz Ferdinand scrapped most of the itinerary, opting only to visit the injured Merizzi at the military hospital.

Sophie, defying calls to travel separately, insisted, «As long as the Archduke appears in public today, I won’t leave his side.» At 10:40 a.m., the convoy departed the town hall, veering west through the bazaar quarter. As Lojka turned onto Franz-Joseph- Straße, Governor Oskar Potiorek barked, «You’re going the wrong way! We’re meant for the Appel Quay!» Lojka braked, the Phaeton stalling and rolling back toward the riverfront, a fatal misstep. Gavrilo Princip, lurking nearby, couldn’t believe his fortune.

Three meters away, the Archduke’s car idled, its occupants framed like targets. Gripping his FN Browning 1910 pistol, Princip fired twice in rapid succession. The first bullet pierced the car door, tearing into Sophie’s abdomen and severing her abdominal artery; she slumped, her head falling into her husband’s lap. The second struck Franz Ferdinand in the neck, slicing his jugular as he rasped, «Sopherl, Sopherl, don’t die, stay alive for our children.» Blood stained his uniform as Lojka reversed frantically, speeding over the Latin Bridge to the Governor’s Palace, the Konak.

Two minutes later, they arrived. Doctors, led by Chief Surgeon Carl Wolfgang, rushed to save Franz Ferdinand, oblivious at first to Sophie’s lifeless form. By 10:55 a.m., both were pronounced dead, Sophie from internal bleeding, Franz Ferdinand from his wounds. Church bells tolled across Sarajevo, and telegraph lines went silent on the governor’s orders. Princip, tackled and beaten by onlookers, survived his botched cyanide attempt, his mouth scorched but his life intact. In custody, he expressed regret only for Sophie’s death.

Grief was not universal. In Budapest, Hungarian elites quietly rejoiced, wary of Franz Ferdinand’s plans to curb their autonomy. Emperor Franz Joseph, nearing 84, received the news at Bad Ischl with chilling detachment. «The Almighty has put right what was in disarray,» he reportedly said, a nod to his strained relationship with his nephew’s reformist circle.

While the Serbian government officially distanced itself from the plot, evidence suggested that elements within its military and intelligence services had tacitly supported, or at least turned a blind eye to, the Black Hand’s activities. Security was notably lax, with only 120 local police deployed.

Austria-Hungary, backed by Germany, issued a harsh ultimatum to Serbia, demanding sweeping concessions. Serbia’s partial refusal, coupled with Russia’s pledge to defend its Slavic ally, triggered a cascade of alliances, France and Britain aligned with Russia, while the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers, plunging Europe into World War I.

The war devastated the Habsburg Empire. By 1918, after four years of grueling conflict, the monarchy collapsed under the weight of military defeat and internal disintegration. The Treaty of Versailles and subsequent agreements dismantled the empire, giving rise to successor states like Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and a diminished Austria. Emperor Charles I, Franz Joseph’s successor, abdicated in November 1918, ending centuries of Habsburg rule.

Source: Sic Semper Tyrannis by Steffen Blaese.